Hello, everyone! It’s translation time again! Today’s offer is a longer one, a translation of the section in Oplosophia* that discusses the use of the sword and cape.

For those unfamiliar with historical uses of garments as off-hand implements in armed defense, this is totally a thing. Honest.

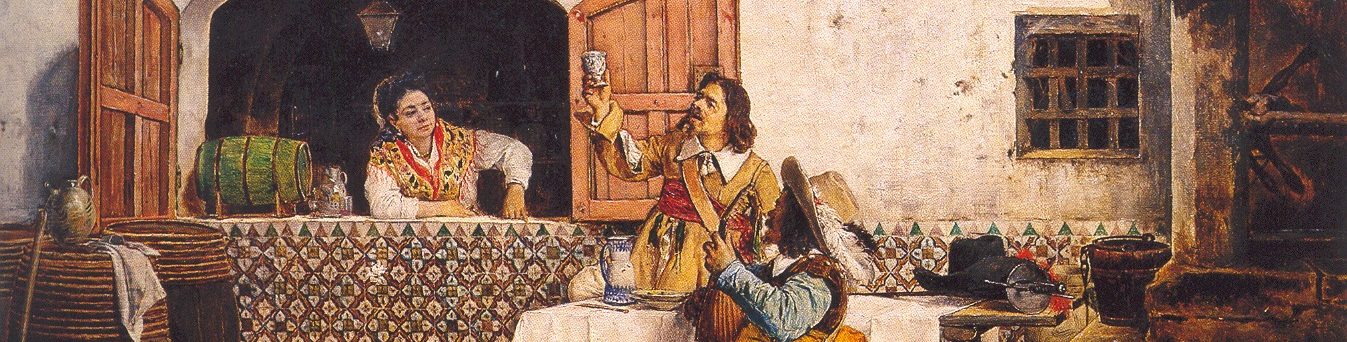

For context, it should be noted that the cape being discussed in this work is the Spanish capa (WARNING: link is to a page in Spanish) which is a very specific kind of garment. Here’s a modern version:

Seseña’s 1901 Classic cape with pomegranate velvet lining. The garment is GORGEOUS but I keep getting distracted by how the model is NOT WEARING SOCKS. It’s driving me nuts. If it’s cold enough for a cape, buddy, it’s certainly cold enough for calcetines. Pónselos, ¿porfa?.

The hemlines of capes contemporary to Oplosophia could tend closer to the ankles. So, we’re talking a lot of fabric.

Anyway, there are less than 1,000 words spent on the subject directly. Which is kind of a shame, ’cause it’d be cool to see diagrams and illustrations, but it’s important to be grateful that we have this manuscript at all.

Because the translations (about 800 words for the English and Spanish each) make this a very long blog post, I’ll address the tl;dr redux of sword and cape and an interesting nugget of capa-related history in a subsequent post. Finally, anything in square brackets [] is my own note.

Modern Spanish translation:

Capítulo Undécimo, Libro Tercero

Cómo usará el Diestro la capa y espada

Las armas que un hombre se encuentre con más frecuencia son la espada y capa, y bien cortejan esta compañía tan común a todos, que con particular certeza se perfecciona la verdadera Oplosofía por instituir los preceptos, o ya guiada de la propia naturaleza, que no es hacer cosa ociosa, ni que deje de ser fundada en razón, ya persuadida de la comodidad y singularidad el Diestro, que no era bien tirando la espada en esas ocasiones en que se deja la capa en los hombros para poder entrar en el peleo, ni menos airoso el largarla, porque[1] eso parecería debilidad, y así junto con la industria introducido por los hombres, y para evitar el enredo que sigue por dejar la capa, y para prohibir el arrojar de la misma, el artificio y compostura con que se hace el brazo izquierdo, se aprovecha de la perfecta Destreza para bien guiar y alisar la capa, dándole a ella de tal manera solamente una vuelta, y que a pesar de la presión puesta por la capa no dejar jalarle el codo, así fijándola sujetada en el dedo pulgar, de forma que la mano no se cubre y queda libre para ejecutar las acciones que se pueden usar después de los atajos, desvíos y las reparaciones que hacen la espada; y se da solamente una vuelta a la capa para que se quede más larga, al fin de mejor impedir las oportunidades de la espada contraria, y forzarle hacer sus círculos más grandes.

Se le advierte al Diestro que cuando se hace la vuelta de la capa, ha de ser fuera de los medios, porque es peligroso con respeto a las vueltas que se dan con el brazo distraen la mayor parte de la intención, y niega que el Diestro usa la espada para conseguir sus efectos; además que aquellos movimientos circulares que se hacen con la capa tapan y alteran la vista en gran medida. No se debe confiar el Diestro que es suficiente presentar la capa comenzando ya a pelear, y puestos los medios, porque la sobra de confianza hace fracasar las obras, y muchas veces ha puesto en peligro la vida. También es así la cólera en estas circunstancias, como es un impulso vehemente de querer castigar aquel de quien se juzga haber sido injuriado, y deja uno de considerar más que a ofender [o sea, el Diestro deja de pensar en su defensa]. Por eso le conviene al Diestro que se prepare fuera de los medios, porque el más seguro escudo contra los sucesos de fortuna es la providencia, y cuando no fuera por otro razón, ser por evitar y mejor considerar que después que se da las vueltas a la capa, el enrollar se obtuvo por mucha conveniencia, porque el demasiado fervor en estas cosas para la mayor parte manda mal.

Todos los golpes que el Diestro da con espada y capa se deben dar por encima de ella, y de su brazo izquierdo; para que en estos actos se puede recogerla junto de los pechos; porque situado en otra parte podrá ella impedir los golpes del Diestro. También de debe preservar por considerables principios el no reparar nunca con la capa (porque esta no sirve de otra cosa más que aplicarse a la espada del contrario después de que se pone al extremo, y es necesario no tomar así nada más que el desvío, y dejar reparos y ataques a la espada) por ser grande el daño que conseguirá el Diestro reparar con ella, como ha pasado muchas veces la espada contraria corta a través de todos los dobleces de la capa, y el brazo se siente el perjuicio de haber acudido al reparo, así como la estocada como el tajo y el revés. No hay que dudar esto pues se ve claramente que mal resisten todas las doblas de cualquier capa a la vehemencia de los golpes de una espada, y la sutileza de su punta, porque ni la defensa de estas dejan de ser muy dificultosas, ni la velocidad de aquellas (ejecutados por buena mano) se repara tan fácilmente.

Y no trato de reparos que se hacen en caso de emergencia, donde la ofensa puede ser mayor sin reparo con la capa, y todavía más con el brazo, en los males ciertos, muchas veces para vencer en parte, se ha de tomar al camino más peligroso, y resolución más arriesgada; porque aquel daño será mayor que vinieron al Diestro descuidado de él; así que la capa en la Verdadera Destreza no puede reparar ni grande ofensa, pues no es más que un impedimento de las liberaciones de la espada contraria, un desvío para los movimientos encaminados sin violencia, y un atajo para después de sujetar la espada.

Modern English translation:

Chapter eleven, book three

The use of the sword and cape by the Diestro

The most frequently encountered arms are the sword and cape, which go quite well together. It’s no good to leap into a fight with the cape just sitting on your shoulders, and it’s just as bad (and not at all graceful) to throw it aside entirely. So, to avoid the embarrassment of keeping the cape on the shoulders, and to prevent the opposite embarrassment of throwing it aside, the Diestro should avail themselves of the perfect Skill to guide and smooth the cape over the left arm, giving it only a single turn over the arm, and despite the tension present avoid letting the elbow get caught up in the cape, holding it securely with the thumb and leaving the hand uncovered as well. This is to leave the arm free to defend after the atajos, desvíos, and parries made by their sword. Again, only give one turn of the cape to leave it as long as possible on the arm, to better interfere with the opponent and cause them and their sword to move in larger circles.

The Diestro should know to spin the cape over the arm when out of measure, because the act of turning the cape distracts most of a Diestro’s intention, and denies the ability to properly take advantage of the sword’s full benefits; also, these circular movements with the cape greatly obscure and alter the Diestro’s ability to see. The Diestro should not feel that it’s enough to present the cape at the start of a fight and within measure, because such overconfidence leads to failure, and can easily put one’s life in danger. Anger, in these circumstances, is a violent impulse to punish the one that has been judged to have injured or insulted the Diestro, which leaves the Diestro thinking of nothing beyond offence. [In other words, not thinking of defence.] This is why the Diestro is advised to prepare outside of measure, because the surest shield against the poor fortune is providence, and when there is no other reason, it should be to avoid and better consider that, after turning the cape over the arm, the maneuver was obtained by sheer convenience, because excessive fervor in these things for the most part leads to a bad end.

All the blows the Diestro gives with the sword and cape should be over the cape, and over the left arm, so that in these actions the Diestro can gather the cape to the chest. If the cape is situated elsewhere, it can impair the blows of the Diestro. Keeping in mind various principles of Destreza, the Diestro should never parry with the cape (because this is of no use aside from applying it to the opponent’s sword after the opponent has overreached, or at least missed and come to the end of his attack; and it is necessary to take no offense this way aside from the desvío, and leave parries and attacks to the sword) due to the great harm that may come to the Diestro should he parry with it, as the sword has, many times, cut through all the folds of the cape, and the arms feels the damage of attempting the parry of the thrust, or the tajo or reves. And there is no doubt because it’s clearly visible how badly the folds of any cape resist the vehemence of sword blows, and the subtlety of its point, because to defend against these is never very easy, nor is the speed of these (executed by a good hand) simple to parry.

And I do not speak here of parries done as a last resort, where the offence may be worse without parrying with the cape, or even the arm alone. In those poor circumstances, to find partial victory, one has to take the more dangerous path, and the riskier resolution, because the harm would be worse if the Diestro received the attacks unaware. Therefore the cape in the True Skill cannot parry great offence, since it is nothing more than an impediment to the liberties of the opponent’s sword, a deflection against movements enacted without violence, and an atajo for using after the subjection of the sword.

So, I’m confused. The manuscript says, in my reading, “attack over the cape and keep it up against your body, but don’t parry with it.” So, what *do* you do with it? It’s not clear what actions the author is suggesting that the cape is actually good for, only that it’s more stylish to carry it on your left arm versus dropping it on the ground. I’m all for style, mind you, but if I’m in a fight to the death then I’ll pay for the cleaning later.

Hi! Sorry for the delay, have been recovering from a 4-day sword event. The cape is used to impair the opponent’s blade, as noted in the last sentence of the first paragraph. It forces the opponent to make larger motions to get around the cape for a clear avenue of attack (though the cape will not stop a direct thrust — that’ll just get the cape pinned to your torso or arm).

It impedes a clean disengage (the opponent’s sword gets caught in the folds of fabric), and if/when the opponent’s sword point comes past your defense without causing harm — for a failed thrust, for example — then the cape arm can control the blade if it went outside of the cape arm.

Generally speaking, though, the clearest way to use the cape is to control the opponent’s blade once it’s been controlled by your sword. Note the last section, though, where Figueiredo admits that it’s A-OK to take a blow on the arm if that prevents a worse attack!

So, do you extend the cloak with your sword? As long as it’s against your body, I don’t see that you get any of the advantages you list – as you say, it won’t stop a thrust, and in that position they don’t need to avoid it.

This is an excellent question, and I’m sorry I’m not being clear. I am hoping in the next few days to get some video of the workshop the Brisbane School of Iberian Swordsmanship ran at Swordplay 2016, where we showed participants how to wear the cape and more importantly, how to prepare it for a fight (both in the common and Destreza style). Generally, the common way of preparing the cape does have you remove it entirely from your body, letting it hang over the off-hand arm more or less in half. The Destreza way to prep it is a little more complicated, and is a work in progress; though Godinho was kind enough to describe in detail how to prep the cape in the pre-Destreza style, we don’t get that benefit from Figueiredo — we had to do some experimenting, cross-checking with period illustrations and some other off-the-beaten-track sources. We believe that the cape came off the sword shoulder, but remained on the off-hand shoulder, and was wound around the arm only once (Figueriedo is adamant about rolling it only once!). Because there’s enough fabric, it hangs on the shoulder, doesn’t tug on the elbow (Figureiredo warns about that, too) and offers a good deal of fabric overhang off the arm to do its intended job.

It’s important to note, though, that in Figueiredo’s order of preference for “armas dobres”, he places it at the very bottom of the list; he knows it’s not the best off-hand weapon, but it is the most likely to be available. That said, BSIS’ chief instructor won a semi-finals bout at Swordplay using sword and cape against a case of swords. (I’ll see if I can get some footage of that, too, ’cause it was pretty cool.)

I do hope to have the video and accompanying commentary ready to go by sometime next week, but I promise I haven’t forgotten, and I hope to get you better answers soon! Thank you for your excellent questions!

Thanks, looking forward to the video!